Johnny Football and the Rule Against Hearsay – Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer (Part 5)

Mr. Prosecutor keeps looking through the rule, knowing something in there should save Mr. Manziel from getting a separate trial. “Here it is,” he says to himself. Rule 803(24), Statement Against Interest: “[a] statement which was at the time of its making so far contrary to the declarant’s pecuniary or proprietary interest, or so far tended to subject the declarant to civil or criminal liability, or to render invalid a claim by the declarant against another, or to make the declarant an object of hatred, ridicule, or disgrace, that a reasonable person in declarant’s position would not have made the statement unless believing it to be true. In criminal cases, a statement tending to expose the declarant to criminal liability is not admissible unless corroborating circumstances clearly indicate the trustworthiness of the statement.” We find people’s statements that subject themselves to ridicule or liability believable, hence the exception. “Statement against interest, your honor,” says Mr. Prosecutor. “The statement to the reporter subjects the reporter to criminal liability.”

Mr. Prosecutor keeps looking through the rule, knowing something in there should save Mr. Manziel from getting a separate trial. “Here it is,” he says to himself. Rule 803(24), Statement Against Interest: “[a] statement which was at the time of its making so far contrary to the declarant’s pecuniary or proprietary interest, or so far tended to subject the declarant to civil or criminal liability, or to render invalid a claim by the declarant against another, or to make the declarant an object of hatred, ridicule, or disgrace, that a reasonable person in declarant’s position would not have made the statement unless believing it to be true. In criminal cases, a statement tending to expose the declarant to criminal liability is not admissible unless corroborating circumstances clearly indicate the trustworthiness of the statement.” We find people’s statements that subject themselves to ridicule or liability believable, hence the exception. “Statement against interest, your honor,” says Mr. Prosecutor. “The statement to the reporter subjects the reporter to criminal liability.”

“Let me see your corroborating circumstances,” replies the judge. The prosecutor starts placing into evidence (outside the jury’s presence) the eBay account of the Autograph Broker, the video the witness claims to have (if it exists), and other evidence. “Admissible as to the Autograph Broker, but you already have that,” the judge rules.

“But judge,” snaps the prosecutor, “the rule doesn’t require corroborating circumstances for admission against Mr. Manziel,”

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

The prosecutor, frustrated that an extra trial might interfere with his upcoming vacation plans, digs through the rules to somehow admit this evidence without allowing Mr. Manziel to force a separate trial. The judge, having similar vacation plans and not wanting to spend county resources empaneling another jury, looks at him. “Any other exception, Mr. Prosecutor?”

The prosecutor, frustrated that an extra trial might interfere with his upcoming vacation plans, digs through the rules to somehow admit this evidence without allowing Mr. Manziel to force a separate trial. The judge, having similar vacation plans and not wanting to spend county resources empaneling another jury, looks at him. “Any other exception, Mr. Prosecutor?” Rules 801 and 803 provide what is non-hearsay and what are exceptions to hearsay. The prosecutor says, “[a]dmission by a party opponent or coconspirator, your honor.” The autograph broker’s lawyer glances down at Rule 801(e)(2) which says, “[a] statement is not hearsay if…The statement is offered against a party and is: (A) the party’s own statement in either an individual or representative capacity; … or (E) a statement by a co-conspirator of a party during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy.”

Rules 801 and 803 provide what is non-hearsay and what are exceptions to hearsay. The prosecutor says, “[a]dmission by a party opponent or coconspirator, your honor.” The autograph broker’s lawyer glances down at Rule 801(e)(2) which says, “[a] statement is not hearsay if…The statement is offered against a party and is: (A) the party’s own statement in either an individual or representative capacity; … or (E) a statement by a co-conspirator of a party during the course and in furtherance of the conspiracy.” First, the right of confrontation would require the ESPN reporter to be on the stand to testify as to his knowledge. So, imagine in a criminal court Johnny Manziel and the autograph broker were being tried for violating NCAA rules or inducing said violations? There they sit with their lawyers at the defense table. The prosecutor asks the ESPN reporter, sitting on the witness stand, “Mr. Rovell, please tell the ladies and gentlemen of the jury what this autograph broker told you he did with Johnny Manziel.”

First, the right of confrontation would require the ESPN reporter to be on the stand to testify as to his knowledge. So, imagine in a criminal court Johnny Manziel and the autograph broker were being tried for violating NCAA rules or inducing said violations? There they sit with their lawyers at the defense table. The prosecutor asks the ESPN reporter, sitting on the witness stand, “Mr. Rovell, please tell the ladies and gentlemen of the jury what this autograph broker told you he did with Johnny Manziel.” The rule against hearsay is one of the fundamental rules of the American justice system. It is very similar, although not completely identical, to the rule requiring confrontation of witnesses in a criminal case, i.e., the right to confront one’s accusers. Our nation’s founders were very disturbed at English prosecutions, such as that of Sir Walter Raleigh, based primarily upon letters from third parties as key evidence. Common sense also dictates that a person telling you what they heard another person say, as if they had observed the events personally, is not in any way as reliable as a first-person recollection of events. Texas Rule of Evidence 801(d) states: “‘Hearsay’ is a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted.” Rule 802 says “Hearsay is not admissible except as provided by statute or these rules or by other rules prescribed pursuant to statutory authority…”

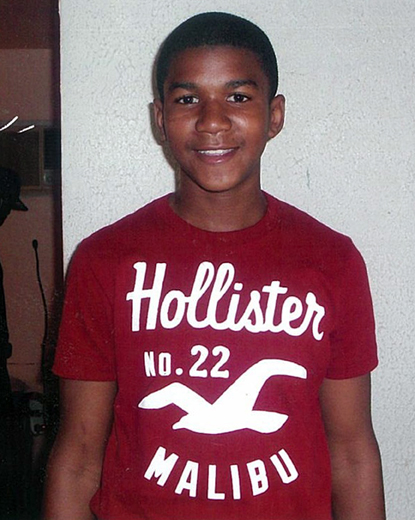

The rule against hearsay is one of the fundamental rules of the American justice system. It is very similar, although not completely identical, to the rule requiring confrontation of witnesses in a criminal case, i.e., the right to confront one’s accusers. Our nation’s founders were very disturbed at English prosecutions, such as that of Sir Walter Raleigh, based primarily upon letters from third parties as key evidence. Common sense also dictates that a person telling you what they heard another person say, as if they had observed the events personally, is not in any way as reliable as a first-person recollection of events. Texas Rule of Evidence 801(d) states: “‘Hearsay’ is a statement, other than one made by the declarant while testifying at the trial or hearing, offered in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted.” Rule 802 says “Hearsay is not admissible except as provided by statute or these rules or by other rules prescribed pursuant to statutory authority…” The Texas Rules of Evidence are modeled after the Federal Rules, and Rule 404 is the main rule governing character evidence. 404(a) outlaws evidence of character simply to prove “conformity therewith on a particular occasion,” I.e. you can’t use character evidence to say simply “he did it before, so he must have done it now.” You can’t generally use a person’s history of theft to prove that he committed a theft on a particular occasion, or evidence that he lied before to prove that he lied on a particular occasion. However, under 404(a) a defendant is allowed to offer evidence of his “pertinent character trait.” I.e., Zimmerman could offer into evidence that he is a peaceful person. At that time, he has opened the door to character evidence that he is aggressive or violent and has so acted on prior occasions. 404(a)(2) also specifically allows evidence of the character of the victim in a self-defense case.

The Texas Rules of Evidence are modeled after the Federal Rules, and Rule 404 is the main rule governing character evidence. 404(a) outlaws evidence of character simply to prove “conformity therewith on a particular occasion,” I.e. you can’t use character evidence to say simply “he did it before, so he must have done it now.” You can’t generally use a person’s history of theft to prove that he committed a theft on a particular occasion, or evidence that he lied before to prove that he lied on a particular occasion. However, under 404(a) a defendant is allowed to offer evidence of his “pertinent character trait.” I.e., Zimmerman could offer into evidence that he is a peaceful person. At that time, he has opened the door to character evidence that he is aggressive or violent and has so acted on prior occasions. 404(a)(2) also specifically allows evidence of the character of the victim in a self-defense case. Character evidence is very important in a criminal case. We want the jury to like our client, and to dislike the person accusing us of an alleged crime or the witness to an alleged crime. However, the rules of evidence generally frown on “trial by ambush,” so there are limits to what one can present. In Trayvon Martin’s case, the Zimmerman team wants the deceased’s Facebook, Twitter and school records to show that Martin was the likely aggressor. If so, it becomes more reasonable for Zimmerman to use force, including deadly force, in self-defense.

Character evidence is very important in a criminal case. We want the jury to like our client, and to dislike the person accusing us of an alleged crime or the witness to an alleged crime. However, the rules of evidence generally frown on “trial by ambush,” so there are limits to what one can present. In Trayvon Martin’s case, the Zimmerman team wants the deceased’s Facebook, Twitter and school records to show that Martin was the likely aggressor. If so, it becomes more reasonable for Zimmerman to use force, including deadly force, in self-defense. Trayvon Martin’s parents are wildly screaming that the privacy rights of their 17 year old “kid” are being invaded by George Zimmerman’s lawyers acquiring Trayvon’s Facebook, Twitter and school records. First of all, what you post on Facebook or Twitter in public has little privacy value. So, be careful what you say on public message boards. Next, school records are private records, but are a gold mine source for criminal defense lawyers and prosecutors researching criminal defendants and criminal witnesses. Defense lawyers in Texas can easily subpoena school records and turn them over to the Court. So can prosecutors, who usually look through a defendant’s school records for evidence of “bad acts” to use against them in punishment hearings.

Trayvon Martin’s parents are wildly screaming that the privacy rights of their 17 year old “kid” are being invaded by George Zimmerman’s lawyers acquiring Trayvon’s Facebook, Twitter and school records. First of all, what you post on Facebook or Twitter in public has little privacy value. So, be careful what you say on public message boards. Next, school records are private records, but are a gold mine source for criminal defense lawyers and prosecutors researching criminal defendants and criminal witnesses. Defense lawyers in Texas can easily subpoena school records and turn them over to the Court. So can prosecutors, who usually look through a defendant’s school records for evidence of “bad acts” to use against them in punishment hearings.