The issue of intoxication and consent came up recently in the Fort Worth Court of Appeals in Anderson v. State, 2012 WL 1222148. In Anderson, two men met two ladies at a bar during a night of drinking. One young lady ended up somehow at the residence of one of the men, along with her friend who appeared to have gone consensually. Anderson claimed they had consensual intercourse, but his accuser said she woke up during unconsensual intercourse and tried to fight him off. The end result was that, “as authorized by the indictment, the jury convicted Anderson of intentionally or knowingly causing the penetration of Miller’s female sexual organ … while knowing that he did so without her consent and that she was either unconscious or physically unable to resist or that she did not consent and was unaware that the sexual assault was occurring. (citations omitted)” The court of appeals noted the established law that “[w]hen assent in fact has not been given, and the actor knows that the victim’s physical impairment is such that resistance is not reasonably to be expected, sexual intercourse is ‘without consent’ under the sexual assault statute. Elliott v. State, 858 S.W.2d 478, 485 (Tex.Crim.App.), cert. denied, 510 U.S. 997, 114 S.Ct. 563, 126 L.Ed.2d 463 (1993).”

We don’t know what happened in the hotel room in San Antonio between these two football players and the alleged victim. What we do know is that just because a person is too intoxicated to resist a sexual encounter, that is not consent to sexual activity. Not only is unconsciousness not consent, being intoxicated to the point of being unaware that the sexual assault is occurring is not consent.

If you or someone you know is being investigated or prosecuted for a crime, call Board Certified Criminal Law Specialist Micah Belden at 903-744-4252.

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

On a night before the Oregon State Beavers played the University of Texas in the Alamo Bowl, two longhorn players went out drinking. At a bar, they met a young woman who eventually invited them back to her hotel room. That was either a sign that the young lady was interested in a night of romance, or a very bad judgment call by a likely impaired young woman who did not realize what she was doing. Early the next morning, she reported to the San Antonio police that she had been sexually assaulted, and did have bruising on her body. Some say the scenario appears to be an obvious “set up” job on athletes, perhaps another Duke University lacrosse-team episode, while others are outraged that an invitation to one’s hotel room could so easily be taken as a sign of consent.

On a night before the Oregon State Beavers played the University of Texas in the Alamo Bowl, two longhorn players went out drinking. At a bar, they met a young woman who eventually invited them back to her hotel room. That was either a sign that the young lady was interested in a night of romance, or a very bad judgment call by a likely impaired young woman who did not realize what she was doing. Early the next morning, she reported to the San Antonio police that she had been sexually assaulted, and did have bruising on her body. Some say the scenario appears to be an obvious “set up” job on athletes, perhaps another Duke University lacrosse-team episode, while others are outraged that an invitation to one’s hotel room could so easily be taken as a sign of consent. The Texas Rules of Evidence are modeled after the Federal Rules, and Rule 404 is the main rule governing character evidence. 404(a) outlaws evidence of character simply to prove “conformity therewith on a particular occasion,” I.e. you can’t use character evidence to say simply “he did it before, so he must have done it now.” You can’t generally use a person’s history of theft to prove that he committed a theft on a particular occasion, or evidence that he lied before to prove that he lied on a particular occasion. However, under 404(a) a defendant is allowed to offer evidence of his “pertinent character trait.” I.e., Zimmerman could offer into evidence that he is a peaceful person. At that time, he has opened the door to character evidence that he is aggressive or violent and has so acted on prior occasions. 404(a)(2) also specifically allows evidence of the character of the victim in a self-defense case.

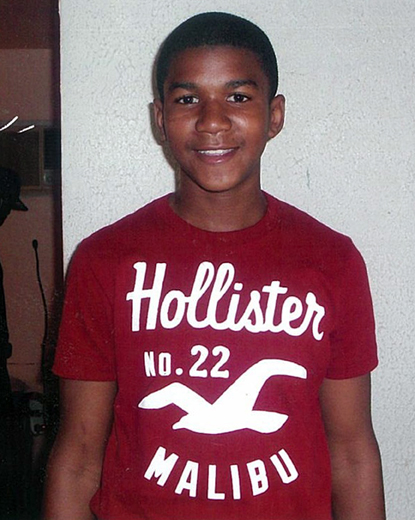

The Texas Rules of Evidence are modeled after the Federal Rules, and Rule 404 is the main rule governing character evidence. 404(a) outlaws evidence of character simply to prove “conformity therewith on a particular occasion,” I.e. you can’t use character evidence to say simply “he did it before, so he must have done it now.” You can’t generally use a person’s history of theft to prove that he committed a theft on a particular occasion, or evidence that he lied before to prove that he lied on a particular occasion. However, under 404(a) a defendant is allowed to offer evidence of his “pertinent character trait.” I.e., Zimmerman could offer into evidence that he is a peaceful person. At that time, he has opened the door to character evidence that he is aggressive or violent and has so acted on prior occasions. 404(a)(2) also specifically allows evidence of the character of the victim in a self-defense case. Character evidence is very important in a criminal case. We want the jury to like our client, and to dislike the person accusing us of an alleged crime or the witness to an alleged crime. However, the rules of evidence generally frown on “trial by ambush,” so there are limits to what one can present. In Trayvon Martin’s case, the Zimmerman team wants the deceased’s Facebook, Twitter and school records to show that Martin was the likely aggressor. If so, it becomes more reasonable for Zimmerman to use force, including deadly force, in self-defense.

Character evidence is very important in a criminal case. We want the jury to like our client, and to dislike the person accusing us of an alleged crime or the witness to an alleged crime. However, the rules of evidence generally frown on “trial by ambush,” so there are limits to what one can present. In Trayvon Martin’s case, the Zimmerman team wants the deceased’s Facebook, Twitter and school records to show that Martin was the likely aggressor. If so, it becomes more reasonable for Zimmerman to use force, including deadly force, in self-defense. Trayvon Martin’s parents are wildly screaming that the privacy rights of their 17 year old “kid” are being invaded by George Zimmerman’s lawyers acquiring Trayvon’s Facebook, Twitter and school records. First of all, what you post on Facebook or Twitter in public has little privacy value. So, be careful what you say on public message boards. Next, school records are private records, but are a gold mine source for criminal defense lawyers and prosecutors researching criminal defendants and criminal witnesses. Defense lawyers in Texas can easily subpoena school records and turn them over to the Court. So can prosecutors, who usually look through a defendant’s school records for evidence of “bad acts” to use against them in punishment hearings.

Trayvon Martin’s parents are wildly screaming that the privacy rights of their 17 year old “kid” are being invaded by George Zimmerman’s lawyers acquiring Trayvon’s Facebook, Twitter and school records. First of all, what you post on Facebook or Twitter in public has little privacy value. So, be careful what you say on public message boards. Next, school records are private records, but are a gold mine source for criminal defense lawyers and prosecutors researching criminal defendants and criminal witnesses. Defense lawyers in Texas can easily subpoena school records and turn them over to the Court. So can prosecutors, who usually look through a defendant’s school records for evidence of “bad acts” to use against them in punishment hearings. Section 7.02(b) states “If, in the attempt to carry out a conspiracy to commit one felony, another felony is committed by one of the conspirators, all conspirators are guilty of the felony actually committed, though having no intent to commit it, if the offense was committed in furtherance of the unlawful purpose and was one that should have been anticipated as a result of the carrying out of the conspiracy.”

Section 7.02(b) states “If, in the attempt to carry out a conspiracy to commit one felony, another felony is committed by one of the conspirators, all conspirators are guilty of the felony actually committed, though having no intent to commit it, if the offense was committed in furtherance of the unlawful purpose and was one that should have been anticipated as a result of the carrying out of the conspiracy.”