On direct examination, neither party can testify as to specific instances of misconduct to show truthfulness or untruthfulness. However, 608(b) states “…[b]ut the court may, on cross-examination, allow them to be inquired into if they are probative of the character for truthfulness or untruthfulness of: (1) the witness; or (2) another witness whose character the witness being cross-examined has testified about.” Specific instances of untruthfulness do not appear to be a major piece of evidence yet, but Kavanaugh’s opponents have claimed that he has lied under oath several times so far. If they were able to prove it extrinsically, they could potentially do so on cross-examination of him.

On direct examination, neither party can testify as to specific instances of misconduct to show truthfulness or untruthfulness. However, 608(b) states “…[b]ut the court may, on cross-examination, allow them to be inquired into if they are probative of the character for truthfulness or untruthfulness of: (1) the witness; or (2) another witness whose character the witness being cross-examined has testified about.” Specific instances of untruthfulness do not appear to be a major piece of evidence yet, but Kavanaugh’s opponents have claimed that he has lied under oath several times so far. If they were able to prove it extrinsically, they could potentially do so on cross-examination of him.

Character evidence is generally inadmissible in Court under Rule 404. But, it plays a much bigger role in criminal cases. A defendant without a criminal history is much more likely to put on evidence of good character or of a pertinent character trait. Rule 404(a)(2) allows, in a criminal case in that “…a defendant may offer evidence of the defendant’s pertinent trait, and if the evidence is admitted, the prosecutor may offer evidence to rebut it; (B) subject to the limitations in Rule 412, a defendant may offer evidence of an alleged victim’s pertinent trait, and if the evidence is admitted, the prosecutor may: (i) offer evidence to rebut it; and (ii) offer evidence of the defendant’s same trait…”

Dr. Kavanaugh may want to offer a pertinent character trait about behaving appropriately around women. However, if so, the Government would be able to offer contrary evidence to his behavior around women to rebut the same. We have heard from his supporters, and we have heard from his detractors that he targeted women for clerkship hiring that “had a certain look.” We also now have a second female classmate saying he stuck his penis in her face at a college drinking party. Dr. Kavanaugh’s mentor has been removed from the Federal Bench for sexually inappropriate behavior, but that is likely too distant to be relevant, unless it could show that Kavanaugh was involved. None of his former clerks have so far come forward against him, but in a real investigation, this would be an important part of the investigation. If he offered any pertinent character trait, these would be offered against him as much as allowed.

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

Sherman & Plano, TX Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

Here, we are dealing with a 35 year-old allegation of sexual misconduct for which no physical evidence would be present due to the age of the case and the nature of the allegation. Additionally, Kavanaugh has not stated that he and Ford engaged in criminal activity, so (B) is out. (C) is interesting as a catchall of “constitutional” admissibility. The only way this would normally come in is as “alternative perpetrator.” evidence. If Kavanaugh attempts to say that third party did the act Ford alleges, and could provide a foundation for the evidence, this sexual conduct could become admissible. But, some Courts have said that this is normally only relevant when identity is an issue. Kavanaugh could argue that intoxication and history make his identity an issue, but his primary defense of fabrication would be confused. So, this wouldn’t be a likely course.

Here, we are dealing with a 35 year-old allegation of sexual misconduct for which no physical evidence would be present due to the age of the case and the nature of the allegation. Additionally, Kavanaugh has not stated that he and Ford engaged in criminal activity, so (B) is out. (C) is interesting as a catchall of “constitutional” admissibility. The only way this would normally come in is as “alternative perpetrator.” evidence. If Kavanaugh attempts to say that third party did the act Ford alleges, and could provide a foundation for the evidence, this sexual conduct could become admissible. But, some Courts have said that this is normally only relevant when identity is an issue. Kavanaugh could argue that intoxication and history make his identity an issue, but his primary defense of fabrication would be confused. So, this wouldn’t be a likely course. Rule 613(b) states that “(b) …[e]xtrinsic evidence of a witness’s prior inconsistent statement is admissible only if the witness is given an opportunity to explain or deny the statement and an adverse party is given an opportunity to examine the witness about it, or if justice so requires…” Thus, the therapist can be called and his notes admitted into evidence to show that Ford made a prior inconsistent statement to him. In he-said/she-said cases regarding adults, such inconsistencies are usually very damaging. I believe this line of attack would be the strongest that Judge Kavanaugh could present.

Rule 613(b) states that “(b) …[e]xtrinsic evidence of a witness’s prior inconsistent statement is admissible only if the witness is given an opportunity to explain or deny the statement and an adverse party is given an opportunity to examine the witness about it, or if justice so requires…” Thus, the therapist can be called and his notes admitted into evidence to show that Ford made a prior inconsistent statement to him. In he-said/she-said cases regarding adults, such inconsistencies are usually very damaging. I believe this line of attack would be the strongest that Judge Kavanaugh could present. The central piece of evidence in this case is Professor Ford’s testimony. She has previously discussed her experience with a therapist, whose notes are different from her recent statements. So, on cross examination, assuming she testifies similar to her recent statements, she would be confronted with the contradictions in her previous statements, if any, with her therapist. From my reading of the news articles, her therapist apparently wrote notes that she claimed there were four people in the room, and one male pulled Judge Kavanaugh off of her. However, her recent statements are that there were two males in the room and she personally escaped after they all rolled off the bed to the ground.

The central piece of evidence in this case is Professor Ford’s testimony. She has previously discussed her experience with a therapist, whose notes are different from her recent statements. So, on cross examination, assuming she testifies similar to her recent statements, she would be confronted with the contradictions in her previous statements, if any, with her therapist. From my reading of the news articles, her therapist apparently wrote notes that she claimed there were four people in the room, and one male pulled Judge Kavanaugh off of her. However, her recent statements are that there were two males in the room and she personally escaped after they all rolled off the bed to the ground. The last-minute presentation of sexual assault evidence against Judge Brett Kavanaugh has put his Supreme Court nomination limbo. Judge Kavanaugh was not my first choice, of those on the Trump list, but I see problems on both sides of the accusation. Sexual assault cases can be the most difficult to defend and prosecute, as they often rely on judging he-said/she-said opposite testimony with no forensic evidence.

The last-minute presentation of sexual assault evidence against Judge Brett Kavanaugh has put his Supreme Court nomination limbo. Judge Kavanaugh was not my first choice, of those on the Trump list, but I see problems on both sides of the accusation. Sexual assault cases can be the most difficult to defend and prosecute, as they often rely on judging he-said/she-said opposite testimony with no forensic evidence.

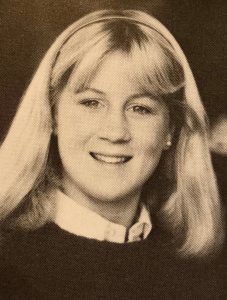

Six years ago, Texas Governor Rick Perry vetoed a ban on texting while driving as an affront to personal liberty. This year, a Republican legislature and Republican governor said that personal liberty needs to be curtailed in the sake of their view of public safety. As of September 1, 2017, texting and in the act driving in Texas is a traffic-ticket level, Class C offense. Although the legislature created several exceptions that will be noted below, an officer who suspects that you are texting and driving, no matter what you are doing, will have a reasonable suspicion that you are violating the law and be able to pull you over for further investigation.

Six years ago, Texas Governor Rick Perry vetoed a ban on texting while driving as an affront to personal liberty. This year, a Republican legislature and Republican governor said that personal liberty needs to be curtailed in the sake of their view of public safety. As of September 1, 2017, texting and in the act driving in Texas is a traffic-ticket level, Class C offense. Although the legislature created several exceptions that will be noted below, an officer who suspects that you are texting and driving, no matter what you are doing, will have a reasonable suspicion that you are violating the law and be able to pull you over for further investigation.

This begs the question, how could encouragement alone ever be the but for of another person actually killing himself? A jury would have to find that but for Ms. Carter’s conduct, the deceased would not have killed himself. Then, the state would have to show also that the concurrent cause (method of death, other factors pushing suicide) were not sufficient on their own to cause death. That would be a very large uphill battle for the prosecutor, because a person who kills themselves by definition caused their own death by some act.

This begs the question, how could encouragement alone ever be the but for of another person actually killing himself? A jury would have to find that but for Ms. Carter’s conduct, the deceased would not have killed himself. Then, the state would have to show also that the concurrent cause (method of death, other factors pushing suicide) were not sufficient on their own to cause death. That would be a very large uphill battle for the prosecutor, because a person who kills themselves by definition caused their own death by some act. Emotions ran high last week as Michelle Carter was sentenced to prison under Massachusetts’ manslaughter law for encouraging her boyfriend to kill himself, which he did. Under the apparent facts of the case, she overcame with words her boyfriend’s reluctance to kill himself due to her crazed need for attention. What would happen if something similar happened in Texas?

Emotions ran high last week as Michelle Carter was sentenced to prison under Massachusetts’ manslaughter law for encouraging her boyfriend to kill himself, which he did. Under the apparent facts of the case, she overcame with words her boyfriend’s reluctance to kill himself due to her crazed need for attention. What would happen if something similar happened in Texas?